All Posts (9261)

SDLC%20112%20Biweekly%20Language%20Learning%20Post%20%237.docx

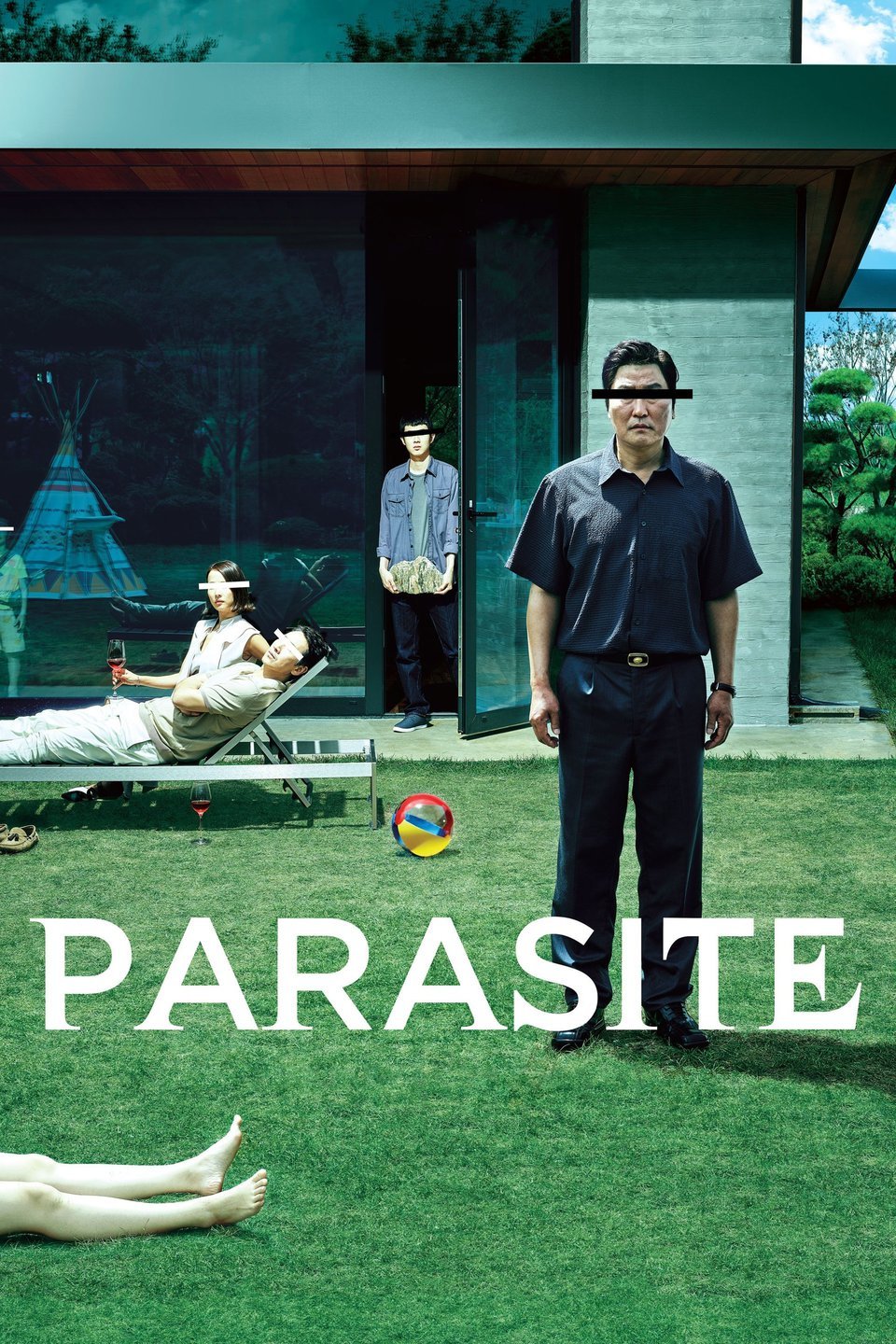

Parasite, a Korean film directed by Joon-Ho Bong, depicts the life of an impoverished Korean family and its unethical efforts to climb the socio-economic ladder. The drama begins when Ki-Woo, the son of the Kim family, is hired to teach English to the Park family’s daughter. Ki-Woo is not qualified whatsoever to teach as he never attended college, but he is hired anyways due to an excellent recommendation by his friend, who was the previous English teacher. After Ki-Woo’s first lesson, he recommends his own sister to be an art teacher for the Park family’s son. This pattern of recommendation is repeated discreetly until the entirety of the Kim family is employed by the rich Park family. Throughout the film, the employed family discreetly works for the wealthy household during the day, while enjoying their unethically earned salary at night.

This film exaggerates the struggles of an impoverished family in Korea, but its point is not to create an accurate depiction. Rather, it tries to highlight a deep and ongoing chasm between the working and wealthy class. The film not only depicts the marginalization of the working class, but the loss of their dignity and voice to change the community around them. For example, the Park family commands sets strong and excessive boundaries when the workers don’t perform their duties properly. The film further highlights the chasm by juxtaposing vocations that are of different social classes. For instance, Ki-Taek, the head of the Kim family, is constantly seen driving Mr. Park, the head of the Park family and CEO of his own successful company. While Mr. Park seems to respect and admire Ki-Taek on the outside, he secretly talks about Ki-Taek’s disgusting scent, describing it as a “special subway smell”.

After watching this film, I found a new interest in the division of classes in South Korea. After further research, I learned that more than 100,000 taxi drivers and chauffeurs are considered laborers rather than contract workers, meaning that their employment status can be hired and terminated at the will of companies that manage these drivers. Drivers are also unable to unionize, preventing them from objecting to any unfair rules passed by their companies. To make matters worse, these drivers are paid less than $1,750 even after being on-call for 24 hours. It’s unfortunate that individuals with low-paying jobs are unable to change careers due to South Korea’s rigid and ineffective education and labor system.

I’m very curious about the steps that the South Korean government is taking to relieve the pressure from the working-class. In 2018, 60 percent of the 100,000 drivers in Korea protested against the rise of ridesharing apps in South Korea. Many of the drivers expressed extreme discontent because of the ridesharing apps’ abilities to eliminate the taxi industry entirely. The government responded by banning ridesharing apps and forced app developers to connect their apps to pre-existing yellow cabs. More research is necessary, but I think South Korea is taking the right steps to ensure the survival of an industry that mostly employs the impoverished working class.

I am excited to study at Yonsei University in Seoul, Korea next semester! Yonsei University was established by American missionaries in 1885, making it one of the oldest universities in Korea. It is also one of the top universities in South Korea and Asia. Most students enrolled at Yonsei University were in the top 1% of their high school graduating class.

Yonsei University is different than UR in several ways. First, it has over 36,000 students and three campuses, which is much larger than the 3,000 undergraduate students at UR. Secondly, it is more competitive. Yonsei University is one of Korea’s SKY universities (Seoul National University, Korea University, and Yonsei University). These three universities are the most prestigious universities in Korea.

I am particularly excited to study Korean at Yonsei because I would like to learn Korean in a formal classroom setting. I am also looking forward to learning in a different kind of classroom setting. At UR, most of the classes are discussion-based. At Yonsei, many of the classes are lecture-style. I want to experience not only a different culture and society, but a different educational setting as well.

There is a difference between how I assume Yonsei University is regarded in Korea and the stories that I have heard from UR students who have studied abroad. Almost all of the students from UR who have studied abroad have told me that there is more school work at UR. At their abroad institutions, their final grades have comprised mostly on their final exam or one paper. I expect there to be less school work throughout my semester at Yonsei than a regular semester at UR. A factor that will contribute to this is that I will have fewer obligations while abroad. I hope to have less school work throughout my semester abroad so that I can travel and truly enjoy the unique culture.

Course registration for Yonsei is in January/February, so I won’t know which classes are being offered next semester until then. In previous semesters, there were classes offered for specifically exchange students. Some that look particularly interesting to me are Korean Popular Culture and Korean Wave, Korean Traditional Music and Culture, Korean Food and Culture, and Understanding K-Pop. There were also classes relating to my leadership major, including Law and Justice, Early Modern Korea and its Historical Sites in Seoul, Business and Society, and Korea-US Relations. Korea is a very popular place to study abroad, largely due to the presence of Korean culture in mainstream media. For this reason, many students who are interested in Korean popular culture study abroad in Korea.

My main purpose for studying at Yonsei University next semester is to explore my Korean heritage, which is an aspect of my identity that I have never truly learned about before. I have never been to Korea, but I have always wanted to visit. Additionally, I want to hear my grandmother’s stories from her life in Korea and coming to the United States. These stories are part of my history too.

When I first decided that I wanted to learn Korean, I wanted to focus on learning basic conversational phrases. My emphasis was also on verbal communication. After 3 months of studying Korean (under several different teachers), I have discovered that my focus has changed. The majority of my time and effort has gone into learning the Korean alphabet. This is very important because it is the foundation for all written Korean. Furthermore, it will help me achieve my future language goals easier. Additionally, I have been learning the technical foundations of the Korean language, rather than just memorizing vocabulary. This also makes sense to me, because it will allow me to really understand the language so that I can use it however I need to. I do not want to be in a position in which I know a lot of vocabulary words and phrases, but do not know how to adapt them to use in different situations. Overall, my process of learning a new language can be illustrated with an exponential graph. The beginning (which is where I am now) is slow and steady, with not much quick progress. However, I am laying the foundation for me to hopefully advance faster.

As I finish this semester with my current language partners, I hope to continue to learn how the Korean language is structured and how it functions. I think it is better to learn grammar with a knowledgeable teacher who can explain it to me. I think that grammar is the most difficult aspect of learning any new language. I actually prefer studying vocabulary because it is easier for me to memorize words than understand new concepts. I can study vocabulary on my own anytime, but I cannot understand new grammatical concepts on my own. For this reason, I will learn the more difficult concepts from my language partners and focus on expanding my vocabulary after the semester ends.

Over Thanksgiving break, I have been enjoying speaking Korean with my family members. My grandmother is pleased that I am learning Korean and is eager to help me in my studies. She is helpful in correcting my pronunciation and teaching me more simple phrases. She is also great to practice with because she is incredibly patient and enthusiastic.

I am really trying to speak Korean whenever I can, because only practice will help me improve in my speaking and listening skills. Jenna told me that students in Korea are very good at reading and writing in English, but they are not as good at speaking and listening. This is because they have to study English in school, but they do not get much practice verbally using the language. I hope to be able to speak and listen in Korean in particular because I predict that I will be speaking and listening in Korean more often than I will be reading and writing. However, I am realizing more and more that the different skills are intertwined, especially with a language that has an alphabet that is new to me.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zhFBVTMAlMvdO6IWnbyqa1vKnxIfBuHC/view?usp=sharing

For my cultural research presentation, I focused on four main genres of Korean music: Korean trot, K-pop, K-rock, and Korean Rap. I then focused on the syntax and morphology of the words in the lyrics of three songs. I found different patterns and techniques that Korean artists use in songs, such as using English words and phrases, rhyme schemes, and altering words to fit the flow of the song. I also found the importance of history and religion and how it has influenced the genres of Korean music. Many western ideals have been incorporated into Korean songs because of the Korean War. Furthermore, I was able to understand the connections between music, culture, and history.

Sources: The different sources I used (pictures, videos, songs, articles) are all below each slide of the PowerPoint attached as a google drive link.

I hoped to learn more grammar and also different cultural aspects of Korean. I think I was able to accomplish these learning goals over the past two weeks.

One activity that we did was talking about our weeks in Korean. This gave us the opportunity to practice some of the conjugating that we have learned in previous weeks. We spoke in very simple sentences but it was good practice. Professor Kim was also able to help us if we were having trouble forming the sentence or conjugating. It was a very helpful activity and I look forward to practicing my Korean outside of the classroom.

Another activity that we did was more practice conjugating verbs in the present tense, polite formal expression. As Professor Kim mentioned different verbs, we would conjugate them on the board. I was really happy that I was able to remember the grammar point we learned last week. I was able to conjugate the verbs on the board and the conjugations were becoming easier with more practice.

Other activities that we did involve learning about the culture. We learned about when to use certain conjugations. Respect is very important in Korean, so it was really helpful to learn when to use certain conjugations and gave me practical knowledge to keep in mind when speaking. We simulated certain scenarios, such as teacher and student, friend and friend, and talked about which conjugation of a verb we would use in that situation. I really liked this activity since it is something that I will have to keep in mind when speaking Korean to people outside the classroom. Another cultural topic we learned about was dating. Professor Kim asked us about the topics we were going to present on for our final presentation and gave us useful information about certain words and topics we can incorporate it in. Professor Kim introduced some new vocabulary words that have to do with dating, and words that are used among the younger generation of Koreans. She also introduced slang words that are commonly used. I thought this activity was very helpful, especially in preparing my final presentation.

I think my strategies have been effective so far. I think that I am slowly becoming more comfortable speaking Korean. I am a lot more comfortable and quick when it comes to short responses in Korean. I will practice my responses, even when people speak to me in English. My Korean speaking friends continue to be encouraging and supportive of my learning journey.

In order to build on what I’ve learned about Korean so far, I hope to learn more vocabulary, especially more verbs. Verbs are very useful and will help greatly expand my abilities to form simple sentences. Learning vocabulary is always important and is necessary if I want to continue progressing into the more complex parts about Korean grammar. I hope that I will have more opportunities to practice my Korean. Not only do I want my speaking skills to improve, but I also hope to continue working on my writing and reading skills. Keeping this in mind, I will seek more opportunities to practice my reading and writing, such as going to a Korean restaurant and trying to read the menu.

Today I am going to write traditional Korean musical instruments. Traditional Korean musical instruments comprise a wide range of string, wind, and percussion instruments. A great number of traditional Korean musical instruments – especially those used in Confucian ceremonies—derive from Chinese musical instruments. There are various kinds of instrument including in Traditional Korean musical instruments. For instance, wind instruments include flutes, transverse, end-blown, oboes, free-reed and trumpets. Also, percussion instruments also have a lot of different types such as Chimes, Drums, Gongs, Cymbals, Wooden Instruments. I will mainly talk about string instruments in this essay.

One of the most important categories of Korean musical instruments is string instrument. Korean string instruments include those that are plucked, bowed, and struck. Most Korean string instruments use silk strings.

For those Korean string instruments are plucked, they are also classified to three different categories, including zithers, harps and lutes.Zithers contains Gayageum (가야금--- a long zither with 12 strings), Geomungo(거문고—A fretted bass zither with six to eleven silk strings that is plucked with a bamboo stick and played with a weight made out of cloth ) ,Daejaeng (대쟁—A long zither with 15 strings), Seul(슬—a long zither with 25 strings), Geum(금 – A 7-stringed zither) and Ongnyugeum(옥류금 – A larger modernized box zither with 33 nylon-wrapped metal strings). And for harps which are no longer used, they only have one instrument which is called Gonghu(공후). There are four subtypes according to the shape including Sogonghu(소공후 – harp with angled sound, 13 strings and a peg that is tucked into the player’s belt), Wagonghu(와공후 – arched harp with a large internal sound box and 13 strings), Sugonghu(수공후—vertical harp without sound box and 21 strings) and Daegonghu(대공후—large vertical harp with 23 strings). Moreover, most of lutes are no longer used. For instance, Bipa(비파- a pear-shaped lute with 5 strings or 4 strings) is uncommon today. Its most modern reactions are modeled on the Chinese Pipa. And Wolgeum(월금) which is a lute with a moon-shaped wooden body, four strings, and 13 frets is also no longer used.

For those Korean string instruments are bowed, they have 2 subtypes called fiddles and zithers. Fiddles include Haegeum( 해금 – a vertical fiddle with two strings), Sohaegeum( 소해금- a modernized fiddle with 4 strings similar to a modern violin), Junghaegeum( 중해금 – a modernized fiddle with 4 strings similar to a modern viola), Daehaegeum( 대해금– a modernized fiddle with 4 strings similar to a modern cello) and Jeohaegeum(저해금 -- a modernized fiddle with 4 strings similar to a modern double bass).

The last type of string instrument is Yanggeum(양금). It is a hammered dulcimer with metal strings, struck with bamboo mallets and derived from the Chinese Yangqin.

For the presentation, I talked about 추석 (Korean Thanksgiving) in three different aspects: nature, family, and traditions. I introduced the time for 추석, how it's related to the harvest, and also different kinds of food people have for 추석. Then, we looked at how 추석 leads to really bad traffic on road, how it could be a really stressful holiday for 며느리 (daughter in law), and how children and teenagers receive pocket money from the elders. Last but not least, I talked about the traditions and activities people do for 추석, mostly related to ancestors. We also discussed different traditions and food people had for 추석.

Reference:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vCaPQJvYwTI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7LPEpPRyiNA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GrnzOZ8FpPk&list=WL&index=7&t=0s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iznKCHgD3AA&list=WL&index=5

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_pu2SRY9XVg&list=WL&index=2

The powerpoint I used for the presentation:

We learned Korean idioms that were used frequently in last two-week classes. At first, I was really confused about the real meaning of those idioms because they were not straightforward. What’s more, idioms always use things that people can see in their daily life to illustrate some important things. In light of this, I think learning Korean idioms is important so that I can get to know more about Korean culture and use Korean idioms in day to day conversations. To be honest, Chinese idioms helped me understand Korean idioms a lot during the classes. Some Chinese idioms have same meanings as Korean idioms that cannot be easily explained by English. I believe that I can really use them in my daily life after understanding them comprehensively. Here are some of the examples of the idioms we have studied in class:

그림의 떡. Literal translation: Pie in the painting. Meaning: referring to untouchable things or something one can only see and not have.

갈수록 태산. Literal translation: As you go there are higher and bigger mountains. Meaning: things are going to get worse and worse, and there will be harder and more difficult barriers to overcome.

미운 놈 떡 하나 더 준다. Literal translation: give one more rice cake to your enemy. Meaning: the more you hate someone the better you should treat them. Aka kill your enemy with kindness.

병 주고 약 준다. Literal translation: to give illness and then medicine. Meaning: first you give someone a punishment then you give them a reward.

누워서 떡 먹기. Literal translation: Like eating cake lying down. Meaning: It is so easy that you can do it while lying down.

작은 고추가 더 맵다. Literal translation: the smaller the pepper, the spicier it is. Meaning: people that look ordinary are better at work/ or have more skills.

지나가던 개가 웃겠다. Literal translation: a passing dog will laugh. Meaning: the joke is so bad, or the situation is so absurd that the dog passing by will laugh.

혼자서 북 치고 장구 친다 / 혼자서 모두 일을 알아서 한다. Meaning: doing everything by yourself.

믿는 도끼에 발등 찍힌다. Literal translation: Be chopped in the foot by the ax you trust. Meaning: used to describe the situation where one is betrayed and hurt by someone or something you trust.

하나를 보면 열을 안다. Literal translation: when you see one, you will know ten. Meaning: able to give examples by looking at one particular case.

하룻강아지 범 무서운 줄 모른다. Literal translation: a puppy isn’t afraid of a tiger. Meaning: one who is ignorant doesn’t understand the situation or how much they should be afraid. One similar phrase in English is fool rush in where angels fear to tread.

This past week, I decided to take on a really big challenge--cooking. It is a tradition when it gets colder out to cook certain foods in Korea, and one of them is a dessert called hoddok (spelled 호떡 in Korean). It’s essentially a fried pancake with brown sugar filling inside and is a classic street food in Korea and is apparently very easy to find and easy to make. I was encouraged by the seemingly simple steps to make the dessert and thought I would use this as a jumping off point for cooking Korean food. I invited a couple friends over to help make and eat the dessert, and I used a box mix that I found at this Korean marketplace and restaurant called New Grand Market.

This is the mix that I used. It had simple instructions on the back in both English and Korean, and since I was cooking a Korean dish I tried to read the instructions in Korean. I found that there were many words that I had never seen before, and ended up having to go back and forth between the English and Korean instructions to understand what the instructions meant. Not being able to even get through simple step by step instructions for cooking made me realize just how small of an area my Korean language skills extended into. I followed the instructions on the back and tried to struggle through what should have been (at least I think) a really easy process.

Step one: mix the pancake mix with water and yeast and mix the batter for around 5-10 minutes continuously. Step two: put rub vegetable oil on hands to prevent the dough from sticking and roll into a small ball. Then, it said to put the brown sugar mix inside the flattened dough ball and carefully wrap the surrounding dough on top of the brown sugar (to create a kind of dumpling shape. I had to look at the English instructions side for the translation of the Korean word for vegetable oil. The direct translation would have been 야채 기름 (yachae gireum) which is literally 야채/vegetable and 기름/oil but instead was 식용유 (shik yong yoo) and I was really surprised at how completely wrong my guess was. Apparently, the yoo in shik yong yoo is the chinese character for oil and is often used instead of the colloquial word gireum. I was surprised to see how integrated Chinese characters still were in Korean language even in modern day. Step three: place the dough on the pan and fry them until the bottom while golden brown and then to press down on the ball gently to create the pancake shape. It then said to flip a couple more times and the pancake would be complete. Overall, this experience was challenging for both my cooking skills and my grasp of Korean. I realized that a lot of words that would be commonplace, everyday language in Korea were completely foreign to me and I might not have realized this without trying to do something completely new like this.

One of the days that I met with my language partner this week, we watched a Korean film called “A Taxi Driver” that came out fairly recently. It was based on a true story about a Seoul taxi driver in 1980, who takes a foreign customer to a Korean town called Gwangju. He initially takes the job because he hears that the foreigner will pay an extremely high rate for the drive, but unknowingly (and unwillingly) becomes involved in the military government’s siege of Gwangju once he gets there. While at first extremely reluctant to help the Gwangju citizens fighting for freedom under the corrupt government, he eventually helps the foreigner (who turns out to be a reporter) get the truth of the crimes against humanity that were occurring in the city, out to global news networks. It was a really really good movie. I was surprised at how positive critic reviews for a foreign film were, and how well made and entertaining the film was. However, one of the most surprising elements of the film was the fact that I got so emotional watching it. There were several brutally violent scenes in the film, many of which were depicting innocent civilians being plowed through by the military during peaceful protest. While part of the grief and anger I felt from watching the movie could be attributed to the sense of injustice that the film incited, it felt like something more was happening. I think the emotions I felt were also from a sense of violated patriotism. The level of pride I felt about a country that I was not a citizen of, and the level of empathy I had for people who I was only really related to through my parents, was really surprising. I had watched historical movies about Korea before. I had watched Korean movies that were emotional before. But I had never felt this kind of wounded pride feeling before--it felt almost like a betrayal. I wondered why this feeling came about. While I’m sure part of it had to do with the sheer skill and craftsmanship of the film in portraying and conveying their message, I think this feeling of connection I had with the people and country in the film had some connection with my increased knowledge about Korea. By learning about Korea’s history and culture, and by learning more and more of the language, I had unknowingly grown more and more intimate with the country. With this newfound intimacy, I think I had also created some of my own expectations and preconceptions about Korea. While I had learned that there were military dictatorships throughout Korea’s history, I hadn’t expected such blatant corruption and abuse of power from a country that I had previously held in such high regard. I had unknowingly put Korea on a kind of pedestal as I learned more about it and became more connected to it. Because it was a country that I had really only learned about through vacations, my parents and through lessons here, I think I fashioned a very two-dimensional image of it. I assumed that Korea could only be a victim because I had heard so many stories of the injustices the people suffered under the Japanese colonization. Watching the film helped flesh out this flat picture I had of the country into one of a nation that was responsible for its own fair share of wrongs and injustices that it had committed to its people.

I have been working with my language partner recently on conversation skills, listening practice, and the number systems. We combined the conversation and listening skills by recording two conversations of my language partner for me to listen to and pick out what I can understand. We then go over what I was unable to hear, or words/grammar points I didn't know. I then listen back to the conversations and practicing hearing the new phrases and making sense of the conversation. This has been an effective strategy in assessing how much I know and identifying things I need to work on. I hope that in the next couple of weeks, I will be able to have an informal polite and a casual conversation with someone about when and where to meet to do something such as studying or seeing a movie. Eventually, I want to try to have an impromptu conversation like this with one of my Korean friends. Next time, we will practice conversing in our group meeting with a written script and go through the same process of working through anything we don't know. It is helpful to have a session one on one with my language partner and one with a group so we may practice together and also get individual help.

We have also been working on the two Korean number systems. At first, I thought I knew Korean numbers fairly well, so I expected it to be more of a review. But I soon realized that the application of the numbers is much more complicated than I thought. One version is derived from Hangul and only goes up to 99. It is used when referring to the number of minutes, people, and years of age. Then there is Sino-Korean which is derived from Chinese and used for dates, money, hours, addresses and any number over 100. The months are also named by counting them. Sometimes I get very confused when I have to remember which way to say 23 for example. If I were to say that I am 23 years old, I would use the Korean derived numbers, but if I were to say the 23rd of March, I would use Sino-Korean. I have been practicing by coming up with a list of random dates and times and practicing writing them out and then saying them out loud. I feel that this strategy is helpful, yet to further my understanding, I will start to write out the date every day along with whatever time it is at that moment. While learning the numbers is a bit frustrating, I think that repetition is really going to help solidify it, so instead of spending time trying to remember what number system I should use, it will already be memorized.

If I have received a research grant to conduct a linguistic study of Turkish and its culture, I want to study the similarity of Turkish and Japanese, because even after learning Turkish for nearly 3 months, I still think that Turkish sounds like Japanese a lot. And I ask my friends who studies Japanese and they thought so. I heard there were a lot of arguments about the reasons, but it seems that the expansion of the Turkish nationality (nomadic horsemen) from Central Asia to East Asia is a strong one. The Altai mountains ranges from the present western Siberia to Mongolia. The Turkish ethnic group has been integrated into this region since ancient times. I believe I would start the research by learning the origins of these two languages and the history of the relationship between Turkey and Japan. After finding the possible historical reasons of why they are similar, I would analyze and compare the phonetic and maybe grammar similarities between these two languages. For example, the grammatical order of Turkish and Japanese is subject + object + verb. In the cases of English and Chinese, it is subject + Verb + object, there is no need to replace the language order when translating Japanese into Turkish. Also, Turkish and Japanese are languages with frequent vowels. The syllables of Japanese are basically "consonant + vowel", and Turkish is similar (there are many cases of consonant + vowel + consonant). Therefore, compared with English, vowels should be heard more clearly. In other words, it can be said that Turkish pronunciation is easy to mark with Katakana, and Katakana pronunciation is easy to understand.

I want to continue my study about Turkish art and its historical context of the last cultural artifact post. For this post, I want to do some research onTurkish architecture and learn more about how history is related to the change in Turkish architectural style.

Turkish lived in dome-like tents appropriate to their natural surroundings at the beginning in their homeland Central Asia. They were nomads at that time. These tents later influenced Turkish architecture and ornamental arts.

At the time when the Seljuk Turks first came to Iran, they encountered an architecture based on old traditions. Integrating this with elements from their own traditions, the Seljuks produced new types of structures. The most important type of structure they formulated was the" medrese". The first medresse

s (Muslim theological schools) were constructed in the 11th century by the famous minister Nizamülmülk, during the time of Alparslan and Melik Shah. The most important ones are the three government medresses in Nisabur, Tus and Baghdad and the Hargerd Medresse in Horasan.

Another area in which the Seljuks contributed to architecture is that of tomb monuments. These can be divided into two types: vaults and big dome-like mausoleums. The Ribati- Serif and the Ribati Anasirvan are examples of surviving 12th-century Seljuk caravanserais, where travelers would stopover for the night. In Seljuk buildings, brick was generally used, while the inner and outer walls were decorated in a material made by mixing marble, powder, lime, and plaster.

In typical buildings of the Anatolian Seljuk period, the major construction material was wood, laid horizontally except along windows and doors, where columns were considered more decorative.

Turkish architecture reached its peak during t

he Ottoman period. Ottoman architecture, influenced by Seljuk, Byzantine and Arab architecture, came to develop a style all of its own. The architectures from this period are also one of my favorite types of architecture.

The years 1300-1453 constitute the early or first Ottoman period when Ottoman art was in search of new ideas. During this period we encounter three types of the mosque: tiered single-domed and sub-line-angled mosques.

The architectural style which was to take on classical form after the conquest of Istanbul was born in Bursa and in Edirne. The Great Mosque (Ulu Cami) in Bursa was the first Seljuk mosque to be converted into a domed one. Edirne was the last Ottoman capital before Istanbul, and it is here that we witness the final stages in the architectural development that culminated in the construction of the great mosques of Istanbul. The buildings constructed in Istanbul between the capture of the city and the construction of the mosque of Sultan Bayezit are also considered works of the early period. Among these are the mosques of Fatih (1470), the mosque of Mahmutpasa, Tiled Pavilion and Topkapi Palace.

In Ottoman times the mosque did not exist by itself. It was looked on by society as being very much interconnected with city planning and communal life. Besides the mosque, there were soup kitchens, theological schools, hospitals, Turkish baths, and tombs.

Below are some pictures of Turkish architectures in Ottoman times.

If I have received a research grant to conduct a linguistic study of Turkish, I would first check the duration and the financial budget of the research. If I have enough time and budget, I would definitely go to Turkey and experience the Turkish culture by myself. Since I want to conduct research about Turkish art and its historical context, there is no better way than appreciating the amazing artifacts displayed in museums by myself. I have several Turkish museums in my list of “must go”. The first is the Ephesus Archaeological Museum. At this charming and well-organized museum, there are not only findings from the ongoing excavations at Ephesus archeological site, but also the artifacts from the Cukurici Mound, the basilica of St John, and the Temple of Artemis. Another one is Chora Church. This medieval Byzantine Greek Orthodox church dates back to around the early 4th century. Also, it possesses some of the most stunning Byzantine frescoes and mosaics. During my trip to Turkey, I would not only do research about those museums and the stunning artifacts in them but also record my whole trip via a vlog, because I want to record everything I see or taste in Turkey.

On the other hand, if I cannot go to Turkey to visit, the best way to do research about Turkish art and its historical context is to talk to my language partner and read books. Although my language partner is not really interested in Turkish art, I am sure that she could provide a different perspective as a Turkish born and bred. As for the book about Turkish art, I think Turkish art and architecture: From Seljuks to the Ottomans would be a good reference. It includes many delicate illustrations and explanations of Turkish decorative arts as well as architecture.

This week we discussed about the Korean history during Japanese colonial. In 1910, Korea was annexed by the Empire of Japan after years of war, intimidation and political machinations; the country would be considered a part of Japan until 1945. In order to establish control over its new protectorate, the Empire of Japan waged an all-out war on Korean culture. Schools and universities forbade speaking Korean and emphasized manual labor and loyalty to the Emperor. It also became a crime to teach history from non-approved texts and authorities burned over 200,000 Korean historical documents, essentially wiping out the historical memory of Korea.

Korean people weren’t the only thing that were plundered during Japanese colonization. One of the most powerful symbols of Korean sovereignty and independence was its royal palace, Gyeongbokgung, which was built in Seoul in 1395. Soon after assuming power, the Japanese colonial government pushed down over a third of the complex’s historic buildings, and the remaining structures were turned into tourist attractions for Japanese visitors.

Though Japan occupied Korea for an entire generation, the Korean people didn’t submit passively to Japanese rule. Throughout the occupation, protest movements pushed for Korean independence. In 1919, the March First Movement proclaimed Korean independence and more than 1,500 demonstrations broke out. The March 1st Movement provided a catalyst for the Korean Independence Movement. Given the ensuing suppression and hunting down of activists by the Japanese, many Korean leaders went into exile in Manchuria, Shanghai and other parts of China, where they continued their activities. Later then, March 1st became the Independence Movement Day, also known as 삼일절 (Samiljeol).

The Japanese surrendered to the Allies in 1945, which ended World War II, led to a time of great confusion in Korea. The country was divided into zones of occupation by the victorious Americans and Soviets. The Soviets and Americans failed to reach an agreement on a unified Korean government, and in 1948 two separate governments were established, each claiming to be the legitimate government of all Korea: the Republic of Korea in Seoul, in the American zone, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in Pyongyang, in the Soviet zone. In 1950, North Korean forces invaded the South. The Korean War drew in the Americans in support of South Korea and the Chinese in support of the North. In 1953, after three years of fighting in which some three million Koreans, one million Chinese, and 54,000 Americans were killed, the Korean War ended in a truce with Korea still divided into two mutually antagonistic states.

By knowing the history of Korea help us gain more insight into a fascinating society and country with the long and rich history.