As with most first year language classes, the hardest part is building your vocabulary. Voca You have to cover the basics, the mundane, the everyday before abstract ideas. We have gone over food, household objects, clothes, and animals in the last month. Now, at the end of lessons, after I recite a paragraph she has prepared for me I also write one out myself using the vocabulary we have learned. Signing it shows her how comfortable I am with the vocabulary at the end of the lesson. And over time she can also see how I’m able to maintain the correct eyebrow positions while expressing myself, using the correct pattern for forming sentences, and moving my body to talk about multiple things at once. Writing everything out lets her check my ability to “gloss.”

Glossing is the written English that follows the same grammatical word order as ASL so as to best put it on paper. It is a transcription not a translation. That is, there is no standard written language for ASL, despite the great strides taken by William Stokoe. Instead we are taking notes on ASL in another language: English. Glossing uses only CAPITAL LETTERS to visually distinguish it from English. Anything not signed, but necessary in the gloss are written in lowercase.

“YESTERDAY me-HELP-him.”

I would not sign ME, HELP, and HIM in sequence to show that action. Instead the sign is one fluid movement where me and him are implied based on the direction of the sign. So, in a gloss we need to understand who was helped and by whom. The unsigned words necessary for comprehension are in lowercase and hyphenated to show the phrase is one sign with a specific meaning.

It is also worth noting that English words do not have ASL equivalents. Rather ASL signs correspond to meanings. It is a symbolic language. There is not a sign for “to.” If you want to sign “I gave a gift to her” it would go “me-PRESENT-her.” The meaning is the same, but you do not sign each individual word.

Another difference between glossing and written English is that verbs do not change tense. Rather, you would sign the time that an event takes place at either the very beginning or the very end of your statement and that would indicate when the event occurred.

YESTERDAY WE SWIM

PAST me-WATCH THAT MOVIE

ONE-WEEK ME GO GALLAUDET

Repetition of a single sign may change it’s meaning. If I sign TREE multiple times, that usually means FORREST. I can then write FORREST in a gloss and know to sign TREE multiple times. However, since I’m still getting the hang of glossing and growing my vocabulary, I usually take the time to write things out multiple times. It reminds me what I need to do when I recite things back to Kimmi.

You can also write out non manual markers in parenthesis. So, if I need to turn my body to show difference in things I am listing or show that I changed actions or show that I was talking to different people, I can write that out (turn body)/(shift left)/(look up). Again, this is more common for beginners than professionals.

When the glosser needs to indicate that they finger spelled a word they did not know how to sign or a new name, is is glossed in all caps with hyphens between the individual letters.

M-A-R-G-A-R-E-T

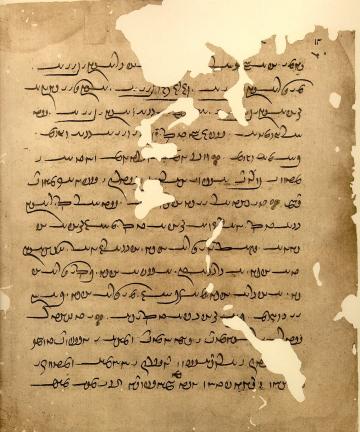

Here is an example of a gloss I wrote the other day:

MY FAVORITE OUTFIT? HAVE BIKE PERSON-MARKER SHORTS, SHOES S-N-E-A-K-E-R-S. COLOR? BLACK HAVE STRIPES PINK. SOCKS - THICK (C Classifier?), WHITE. S-W-E-A-T SHIRT FROM MY SCHOOL NAME? UNIVERSITY RICHMOND. SHIRT HAVE SCHOOL NAME. I LIKE MY CLOTHES. WHY? WARM and (turn body) LOOK SAME PRINCESS D-I-A-N-A