SDLC F22 Discussion Posts

Post #10

1) Read: ScienceLine, “Are Bilinguals Really Smarter?” 2) Read: NYT: “Why Bilinguals are Smarter”

Imagine that you have received a research grant to conduct a linguistic study of your target language and culture. How would you get started, and what would you investigate? How would different structural components presented in class appear in your work?

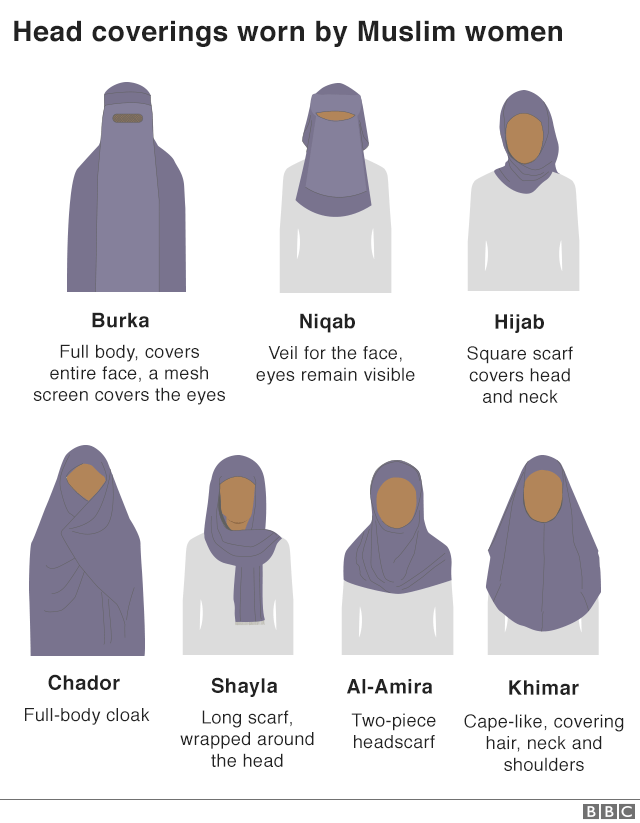

I would want to investigate modern slang in Iran, especially around the government and censorship, and also how the modern-day population views Islam. I would first try to talk to the family and/or contacts I have in the U.S., as it might be much harder to discuss such topics in Iran. I would also try to reach out to any known researchers in the field. I know from limited experience that a large number of (particularly younger) Iranians do not practice Islam, and a more-or-less common form of protest is improperly wearing the state-officiated hijab. I recall one of my cousins saying you could tell what people in Iran were actual Muslims based on how they wore the hijab, as many women still show their hair (but not enough to get detected by the morality police). Eventually, after my Farsi was proficient enough and I knew enough nuances about the culture -- especially as it concerns politics, I would go to Iran and try to discretely gather opinions on the topic. This endeavor is rather fantastical, as many people might be too afraid to talk so openly about the government. Communicating with technology would be out of the question, as the Iranian government monitors internet interactions.

Post #9

How have you started writing in the target language? Do you prefer to type or write freehand? Have you started to see patterns emerge in the structures between words, clauses, and sentences? What is the relationship between simple and complex sentences? How does your knowledge of parts of speech, government, and agreement affect your ability to communicate in written contexts? Provide a sample of several short meaningful writing exercises from your target language.

I have dabbled in writing in Farsi (my target language), mostly out of curiosity. The script is written and read from right to left, and the main strokes are completed first within one 'word' (a little complicated how that is divided up), then additional strokes are added (dots and slashes. Many verbs are compound, meaning they can be formed by taking a noun or a verb and another verb and making a new verb. Here are some examples of this:

- دیدن کردن (didan kardan) to visit

- دیدن (didan), to see

- کردن (kardan), to do

- حرف زدن (harf zadan), to talk/speak

- حرف (harf), letter/speech

- زدن (zadan) to hit, to touch

There are no gendered articles in Farsi, in fact, there is no word for the pronouns he or she, only it (though there are varying degrees of politeness). The pronoun "it" is actually hardly used, it is much more common to refer to someone by their name or relation, or just leave it out of the sentence and only conjugate the verbs in the third person.

Post #8

1) NYT “Tribe Revives Language on Verge of Extinction” 2) Watch the 2007 Interview with David Harrison, “When Languages Die.”

How do languages go extinct?

Increasing globalization and rising global communication have, almost ironically, caused a severe degradation in the diversity of language. Globalization, more often than not, leads to homogenization, as cultural intermingling leads to cross-cultural change. Hegemonic cultures (such as Western/European cultures) often lead this homogenization, as various forms of media signal the hegemonic culture as a model one. This cultural phenomenon parallels what happens to the languages within the respective cultures.

Respond to the readings, and reflect on what happens when a language dies. How can linguists help preserve a language? Can a ‘dead’ language ever be brought back to life? What efforts are currently underway to document linguistic diversity?

One crucial aspect of reviving a language is creating an immersive environment so that language can be quickly absorbed by new learners. Though learners can study a language for a long period of time, they might never reach the same level that they would in an immersive environment (often in a shorter period of time). This inherently answers the next question, as linguists can help foster these immersive environments, as the more easily accessible they are, the more motivated learners will be to pursue them.

The question of whether or not 'dead' languages can be revived depends heavily on how one defines a 'dead' language. If there are no surviving records of the language, be it speakers or scripts, this would make reviving it extremely difficult, as there might be no way to tell if its revival is accurate to the original (i.e. it is possible a new language could be made with the same name as the old, but we would have no way to tell).

Post #7

No Readings

Go back and watch the recording of your presentation of your learning plan on the class PanOpto collection on Blackboard. Comment briefly on how things are going. What has changed? How have you incorporated materials and insights from class into your efforts? Have discussions regarding language structures and learning strategies helped you to understand the target language and culture? If so, how? Reflect on your language learning so far. How would you describe the relationship between language and culture? What do you need to do to improve your communicative competence? Based on the readings by H.D. Brown, what kinds of competence are emphasized in your plan?

A lot has changed politically in Iran. It has been much harder to talk about current events because my language partner fears the Iranian government is monitoring our calls. In terms of materials, it has been much slower than I had anticipated. The intermediate lessons on the website that I use, PLO (Persian Language Online), use much more intricate grammatical structures that are not as intuitive to me. The vocabulary is more abstract, so it makes it more difficult to remember/recall fluidly. I have incorporated more lessons from class. Our current unit on phonology has made it easier for me to understand the articulation points I should be striving for.

I do not think I am quite at the level yet where I can connect the language structure to culture; that being said, however, the influence of Arabic on Farsi (Arabic loanwords, script, etc.) portrays the intermixing of the two cultures and the integration of Islam in modern-day Iran.

Through my learning of Farsi, my understanding of the linkage between language and culture deepens. Especially considering the political circumstances in the country, the movements in the language (such as attempting to reduce Arabic loanwords, despite Arabic being the dedicated language of the Quran) are tied with current political movements (reduction of Arabic can, in a way, show how some members of society -- especially women -- are moving towards a more secular state).

Post #6

Readings: 1) “What is a Language Family” by Kevin Morehouse 2) “Family Tree of Language Has Roots in Anatolia, Biologists Say” by Nicholas Wade

Reflect on the history of your target language. To what language family does it belong? What sounds, words, and structures exemplify periods of contact with other cultures?

Farsi specifically belongs to the Western Iranian group of the Iranian languages, which is in the Indo-European language branch. One influence can be seen in the very name of the language. Arabic has had a large cultural (and thus linguistic) influence on Iranian culture. An aspect of Arabic is that there is no [p]. This is not the case in Farsi, the original name being "Parsi," but was changed because [f] does exist in Arabic. Another Arabic influence can be seen in the Farsi writing system. Though the alphabets are not identical, there are some letters in the alphabet (س ص ث = [s], or ز ذ ظ = [z] to name a few) that all represent the same phone/sound; however, in Arabic, these letters represent different sounds/phones, which do not exist in Farsi.

Read Post #5 for more information on the Arabic invasions and Farsi.

How do these considerations enhance your understanding of the target language and culture in terms of their associated historical origin, development, and contemporary realization? and pragmatic questions of usage?

As I've encountered in my learning, occasionally we (my Language Partner & I) will run into Arabic words, and consequently, small grammar points associated with those words (mainly plurals or pronunciation). I will make more of a point to keep track of these Arabic loanwords, and possibly research some of the relevant grammar associated with them.

How do languages change over time? How do linguists track, predict, and extrapolate these changes?

Language mainly changes the following ways: change in phoneme pronunciation, borrowing words or features from other languages, and analogical change (e.g. "inflammable" changing to "flammable"). In historical linguistics, linguists can examine an older/dead language by tracing the phonetic changes in modern, related languages backwards, allowing them to recreate how the original language may have sounded.

Post #5

Readings: 1) “Communicative Competence,” pp. 218-243 from Principles of Language Learning and Teaching by H.D. Brown

Do some preliminary research on what interests you about the target culture and describe how this topic relates to language. Do you need any special vocabulary or linguistic knowledge to engage this topic? If so, have you included objectives in your learning plan to engage this topic?

I am mainly interested in learning more about the Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, by Iranian poet Abolqasem Ferdowsi --specifically its cultural and linguistic significance. The Shahnameh arguably saved and preserved the modern (written) form of my target language, Farsi.

In the 7th century, the Sassanian Empire in Iran fell to an Arab invasion. For the next two centuries, Iranians were persecuted for their faith (Zoroastrianism, one of the first monotheistic organized religions, was the main religion in Iran before Islam), libraries burned, and the use of Farsi (written and spoken) was all but silenced. In Iran, this period is known as the 'two centuries of silence.' Farsi, Zoroastrianism, and any other Iranian culture were at risk of extinction from the Arabic language, government, and Islam.

Ferdowsi finished and rewrote the Shahnameh, which comprised almost all pre-Islamic traditions, legends, and history, in a relatively pure form of Farsi without the use of Arabic or other loanwords. Ferdowsi and his accomplishments are revered in Iranian culture, and the Shahnameh is seen to many Iranians as the savior of modern-day Farsi and Iranian culture.

Post #4

Readings: 1) G. Hudson, “Phonetics” in Essential Introductory Linguistics, pp. 20-42.

What is the difference between sound and spelling?

Spelling refers to a specific language's method of representing written communication; this can include representations of sound, but these rules often have exceptions and can be a static representation of sound.

Sound refers to the specific phones and pitch in a language, "speech" being defined as "a sequence of phones" (20).

Why is this distinction significant for your language-learning efforts?

It is important to understand that we must be cautious when reading so as to not use our target language's writing system as a guide to pronunciation. Writing can be deceiving and omits important factors, such as meter or what syllables are stressed.

Describe the phonetic inventory of your target language. Are there sounds in your language that don’t exist in American English? If so, provide several words and their phonetic transcriptions of words as examples to support your argument.

- the fricative [ʁ]

- example: " داغ " \ˈd̪̊ɑʁ̥\ = "hot" (like a desert)

- plosive uvular stop [q]

- example: " قلب " \ˈɢ̊alb̊\ = "heart"

- post-alveolar stop [d͡ʒ]

- example: " به ویژه " \b̊eh̬ v̊iˈʒe\ = "especially"

Farsi also has "r" trills and taps, which almost every "r" adhers to.

What do you need to know about the sound system of your target language?

I have already practiced the phonetics of my language extensively, though I can always get better. Funnily enough, I seem to struggle the most with American-English /r/'s; I've always found it easier to tap or even trill.

How will you acquire the ability to discriminate differentiated segments in your listening, and to produce these sounds in your speech?

Because I have been listening to Farsi for many years, I am already decent in my ability to discriminate between the different sounds in Farsi.

Post #3

Readings: R1) D. Crystal, How to Investigate Language Structure, R2) J. Aitchison, Aitchison's Linguistics

Refer to the diagram on page 9 in Aitchison’s linguistics (see figure to the right). How do you combine different disciplinary perspectives to formulate a more holistic understanding of your target language? Do you give preference to one disciplinary approach over the others?

As of right now, I am mainly concerned with "Languages"/"Applied Linguistics," mainly due to the fact that I am still a beginner in my target language; thus, I am most focused on building a strong foundation in the core of Aitchison's circle, phonetics, phonology, syntax, and beginning to develop semantics and pragmatics.

I could argue I study my target language through a stylistics/literature lens (albeit simple literature). This helps provide a more holistic approach to my target language, Farsi, because the language is divided in formal/written language -- the "Literature" portion (which I am exposed to through reading my lessons -- "Literature"), and the "Languages" portion -- when I read dialogues using more casual/colloquial Farsi, or I practice conversational speaking with my Language Partner.

How will your knowledge of language structures and disciplinary methodologies inform the trajectory of your learning plan?

Again, as of right now, I am mainly focusing on the first 3-4 rings in Aitchison's figure. Because of my heritage, the pure phonetics of my target language perhaps comes easier than if I were studying a completely foreign language/culture. Nonetheless, I am struggling much more with syntax, as Farsi operates in a mainly Subject + Object + Verb (SOV) sentence structure, while English almost exclusively uses SVO (or OVS in the past tense). This and the extensive verb conjugations mean I am dedicating much more time to syntax.

Post #2

Summarize some of the main ideas behind Figuring Foreigners Out and the Hofstede Dimensions of Culture (source 1) (source 2) (source 3).

Gert Hofstede developed a model (a series of choropleth maps) delineating how various cultures (and their values) affect their respective workplace values.

In his research, he initially developed four choropleth maps: Power Distance Index (PDI), Individualism (IDV), Masculinity (MAS), and Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI).

PDI (image above) "focuses on the degree of equality, or inequality, between people" (source 1). A large distance (dark green) represents little upward mobility and clear class division, and a small distance (light green) represents high upward mobility and fluid class division.

IVD (image above) "focuses on the degree the society reinforces individual or collective, achievement and interpersonal relationships" (source 1). High individualism (dark purple) represents an emphasis on individual rights and less-family-oriented (looser) relationships. Low individualism (light purple/white) represents an emphasis on collectivism and strong, family-oriented relationships.

MAS (image above) "focuses on the degree the society reinforces, or does not reinforce, the traditional masculine work role model of male achievement, control, and power" (source 1). High masculinity represents a high degree of gender differentiation, with males being the dominant force of power. Low masculinity/femininity represents a low degree of gender differentiation, with females sharing equal status with males.

MAS (image above) "focuses on the degree the society reinforces, or does not reinforce, the traditional masculine work role model of male achievement, control, and power" (source 1). High masculinity represents a high degree of gender differentiation, with males being the dominant force of power. Low masculinity/femininity represents a low degree of gender differentiation, with females sharing equal status with males.

UAI (image above) "focuses on the level of tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity within the society - i.e. unstructured situations" (source 1). A high UAI indicates a low tolerance for ambiguity, and a low UAI indicates leniency for a variety of opinions.

UAI (image above) "focuses on the level of tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity within the society - i.e. unstructured situations" (source 1). A high UAI indicates a low tolerance for ambiguity, and a low UAI indicates leniency for a variety of opinions.

The last two were developed later in his research.

LTO (Long-Term-Orientation) (image above) "focuses on the degree the society embraces, or does not embrace, long-term devotion to traditional, forward thinking values" (source 1). High LTO shows a reluctance to cultural change, and low LTO shows fluidity in cultural traditions.

LTO (Long-Term-Orientation) (image above) "focuses on the degree the society embraces, or does not embrace, long-term devotion to traditional, forward thinking values" (source 1). High LTO shows a reluctance to cultural change, and low LTO shows fluidity in cultural traditions.

The last map (image above) compares indulgence and restraint. "In an indulgent culture it is good to be free. Doing what your impulses want you to do, is good. Friends are important and life makes sense. In a restrained culture, the feeling is that life is hard, and duty, not freedom, is the normal state of being" (source 2).

Do you predominantly agree with these assessments? Are there any statements, generalizations, and opinions expressed in the reading that you find problematic?

I think some of these values will differ generationally. Many are also simplified; a culture could have different values for different aspects (political power vs. economic status). These dimensions also do not take into account that various different cultures may reside in one national region. Take the U.S. for example, I would assume Hofstede aligned the U.S. according to its Western citizens; it discounts many different experiences and people groups.

Post #1

Readings:

- Crystal, D.: How the brain handles language

- Crystal, D.: How we mean and How we analyse meaning

Reflect on the readings:

Do you have any questions about the texts? Are there any claims that you find problematic? Do you think language is a purely biological phenomenon?

Crystal suggests that language was biologically induced through the physical ability of speech, and later innovated culturally through writing. Moreover, no, language in its modern form is not solely a biological phenomenon.

What parts of the brain are most important for the production and comprehension of speech?

In general, people who are right-handed depend more heavily on the left hemisphere for language processing, but the right hemisphere still plays a part. This question depends on the validity of the theory of cerebral localization, which states specific areas in the brain have specific roles in the production & comprehension of speech.

How do you conceptualize or process meaning?

Crystal states that a more effective way to analyze meaning in language is to simply analyze how meaning is expressed in language. This includes, but is not limited to: word choice, grammatical structure, sound/intonation (auditory difference between a questioning statement and a clarifying statement), spelling, and the expected answer to a statement (taking a statement literally or answering the statement's meaning).

Crystal also states "isolated words do not lack meaning, Rather, they have the potential for conveying too much meaning." He believes a crucial aspect of meaning is not simply a single word, but how all aspects of conveying meaning intermingle with one another.

Do these readings inspire any special insights or motivations that could help advance your foreign-language abilities, retention, and recollection?

These readings help learn ways of parsing out specific connotations (meanings) of various words in the target language, as opposed to assuming the English counterpart (if it exists) holds an equivalent meaning. The cultural aspects of language lead to meanings that cannot be translated in a single word, making the relationship between words in a translation all the more crucial.