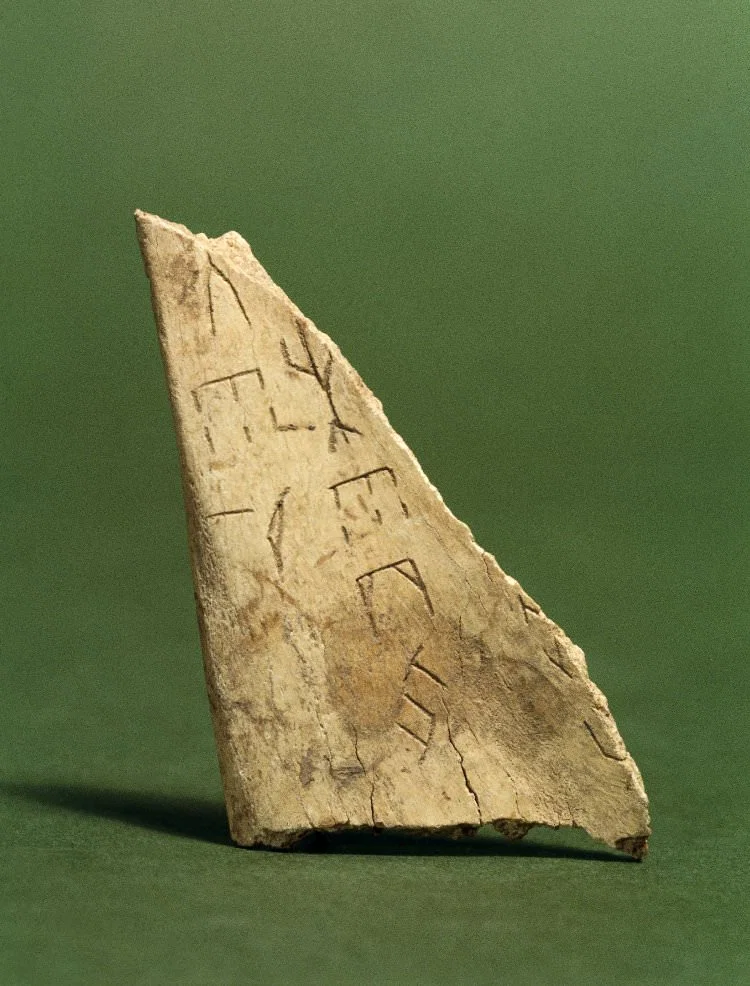

Oracle bones are commonly recognized today as incredibly important artifacts that have provided key insights into the development of the Chinese language, as well as Chinese history. It is difficult to identify when they were first discovered, but a late-19th century scholar named Wang Yirong is generally credited with recognizing the markings he observed as ancient writing. Previously, the bones had been used in medicine, and the inscriptions had not really been recognized as written messages. Around the same time, several other scholars began to publish writings on their translations of the inscriptions and investigate where the oracle bones were coming from; many were found by farmers around Henan. Usually, the oracle bones were made with turtle’s shells or ox bones. Clients (who were often, though not always, wealthy and could more easily afford consultations) would visit a diviner or priest and ask a question about an action or decision to pursue. Characters relating to their question would be written on the bones, and the diviners would then drill a hole into the bone, apply a hot poker until it cracked, and read the future based on the direction of the cracks. The questions often revealed matters of importance during the Shang Dynasty in both government and daily life, as they were consulted by royals hoping to predict events like the result of an important battle or farmers wanting to know about coming harvests, and they also revealed prevalent religious beliefs based on the attitudes towards connecting with the spiritual world. They were carefully marked with the dates of the questions asked and the people who asked and answered them; they also recorded the given answer and the result of the prophecies (whether or not they became true), which provided important historical records not only about the goals and plans of people of all different backgrounds and experiences, but also about businesses, cities, government decisions, and day-to-day activities.

The use of oracle bone script dates back to the fourteenth century B.C., and it can still be connected to language today – the Shang dynasty inscriptions in particular seem to be most commonly realized as one of the earliest forms of Chinese writing. There is some debate over markings on neolithic pottery, and sites describe them differently (one calls them “the precursors of Chinese writing”) but seem to focus mostly on the Shang Dynasty discoveries. Some of the characters are fairly pictorial, but phonetics also play a role in the construction of characters, and these combinations have evolved over time. Some words are pronounced similarly and have similar depictions, and some have combined different characters or symbols across time and vocabulary to construct more and more meanings centered around main ideas. The characters for the numbers one, two, and three have stayed much the same – they are one, two and three horizontal strokes, respectively. The character for rain looks like water droplets under a horizontal stroke; it has changed somewhat, but is still identifiable. This character is labeled “ideographic” rather than simply pictographic, although its depiction of the idea it represents is still evident. Research on the development of Chinese language is still being conducted – one author hopes to find connections to older forms of writing given the “maturity” of the oracle bone script system. It is still important and informative to consider the relationships between the words used today and the words used thousands of years ago, and how our ideas and representations of them have evolved.

Replies